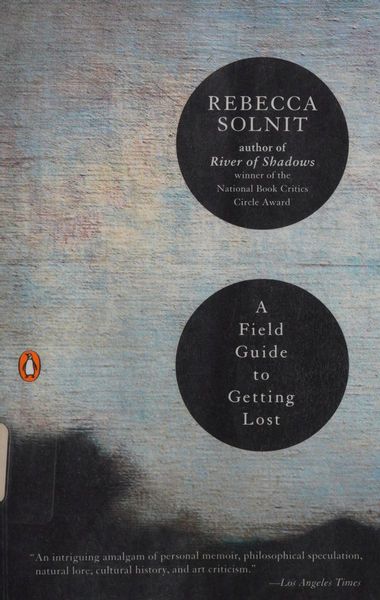

A Field Guide to Getting Lost

A series of autobiographical essays draws on key moments and relationships in the author's life to explore such issues as trust, loss, and desire, in a volume that focuses on a central theme of losing oneself in the pleasures of experience. By the author of River of Shadows and Wanderlust. Reprint. 25,000 first printing.

Reviews

Cecilie Spangsberg@ceciliespangsberg

Megan Parrott@meganparrott

Kent Reymark Tocayon@reyreykenny

Michelle@jackalope

Nick Gracilla@ngracilla

Sloan, Kara@kayraw

Amelia Hruby@ameliajo

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Jade Flynn@jadeflynn

Tara King@sparklingrobots

Sameer Vasta@vasta

Joylyn yang@joylyn

Quentin Gibeau@xmas_gonna

mina@glowinglune

Robin Howie@robinhowie

Nick Truden@youngdust

Lindy@lindyb

Emma Bose@emmashanti

andrea valentina @virginiawoolf

Melissa Railey@melrailey

azliana aziz@heartinidleness

Cassie B@partialtruth

Becca M@becmarotta

Hannah Brennan@hbrennan

Highlights

Meera@meerasuwaidi

Page 16

Meera@meerasuwaidi

Page 14

Meera@meerasuwaidi

Page 11

Meera@meerasuwaidi

Page 10

ash@titaurapopsicle

Page 16

dima@dima

Page 188

dima@dima

Page 187

dima@dima

Page 186

dima@dima

Page 182

dima@dima

Page 182

dima@dima

Page 179

dima@dima

dima@dima

dima@dima

dima@dima

dima@dima

dima@dima

dima@dima

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Dora Tominic@dorkele

Dora Tominic@dorkele