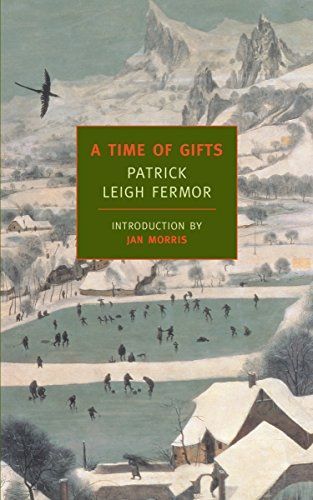

A Time of Gifts On Foot to Constantinople: from the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube

In 1933, at the age of 18, Patrick Leigh Fermor set out on an extraordinary journey by foot - from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople. A Time of Gifts is the first volume in a trilogy recounting the trip, and takes the reader with him as far as Hungary. It is a book of compelling glimpses - not only of the events which were curdling Europe at that time, but also of its resplendent domes and monasteries, its great rivers, the sun on the Bavarian snow, the storks and frogs, the hospitable burgomasters who welcomed him, and that world's grandeurs and courtesies. His powers of recollection have astonishing sweep and verve, and the scope is majestic.

Reviews

Ned Summers @nedsu

Andrew John Kinney@numidica

Vicky (A City Girl's Thoughts)@acitygirlsthoughts

Donald@riversofeurope

Teaghan Grayson@teaghan

Alexander Lobov@alexlobov

Liz Prinz@prinzy

Max Bodach@maxbodach

Christopher McCaffery@cmccafe

Trevor Berrett@mookse