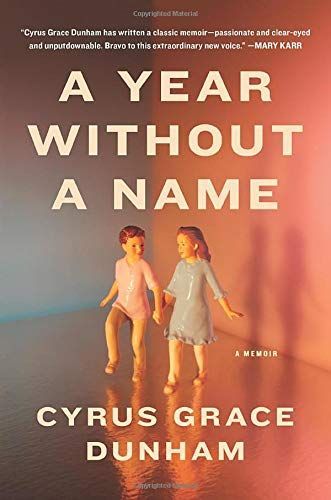

A Year Without a Name

A genderqueer coming-of-age story of stunning frankness and passion, from a remarkable new talent. When I figured out how to spell the words I held in my mouth, I wrote them over and over until they filled up the page. "I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay I'm gay." Then I ripped the paper up and flushed it down the toilet. Cyrus Grace Dunham (who happens to be Lena's sibling) has always known that they didn't fit on either side of the gender binary. As a child, they used to slick their hair back and pose in front of the mirror, "lifting my chin up like men in magazines" and privately calling themselves "Jimmy." But they had no language to express their profound sense of alienation, until relatively recently, when they embarked on a search for a new name. Writing with disarming emotional intensity in a voice all their own, Cyrus Grace chronicles a childhood in a family of artists with larger-than-life personalities, bouts of gender dysphoria and obsessive-compulsive disorder, soaring romantic adventures, and faltering first forays into adult life, all the while exploring the complex family relationships that lay our foundations, constrain us, and inform our capacity to love. Signaling the arrival of a boldly original writer with a knock-out "page presence," A Year Without a Name is a searching, lyrical memoir of coming to terms with genderqueer identity as well as a heartrending portrait of the terror, excitement, and uncertainty of youth.

Reviews

Lindsay@schnurln

Audrey Kalman@audkal

aem@anaees

Tori W.@vanillie

Highlights

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln

Lindsay@schnurln