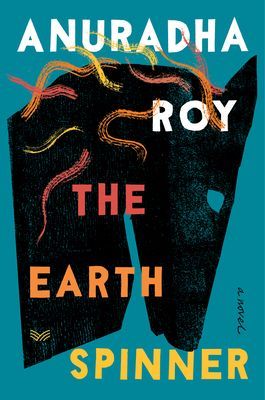

The Earthspinner A Novel

From the critically acclaimed, Booker Prize-nominated author of Sleeping on Jupiter and All the Lives We Never Lived, an incisive and moving novel about the struggle for creative achievement in a world consumed by growing fanaticism and political upheaval. One night, Elango has a dream that consumes him, driving him to give it shape. The potter is determined to create a terracotta horse whose beauty will be reason enough for its existence. Yet he cannot pin down from where it has galloped into his mind. The Mahabharata? The Trojan horse legend? His anonymous potter-ancestors? Once it’s finished, he does not know where his creation will belong. In a temple compound? Gracing a hotel lobby? Or should he gift it to Zohra, the woman he loves, yet despairs of ever marrying. The astral, indefinable force driving Elango toward forbidden love and creation has unleashed other currents. He unexpectedly falls into a complicated relationship with a neighborhood girl who is beginning her bewildering journey into adulthood. He is suddenly adopted by a lost dog who steals his heart. While Elango’s life is changing, the community around him is as well, but it is a transformation driven by inflammatory passions of a different kind. Here, people, animals, and even the gods live on a knife’s edge and the consequences of daring to dream are cataclysmic. Moving between India and England, The Earthspinner reflects the many ways in which the East and the West’s paths converge and diverge in constant conflict. Anuradha Roy breathes new life into ancient myths, giving allegorical shape to the terrifying war on reason and the imagination waged by increasingly powerful forces of fanaticism. An epic that is a metaphor for our age, The Earthspinner is an intricate, wrenching novel about the transformed ways of loving and living in an increasingly uncertain world.

Reviews

Deepika Ramesh@theboookdog