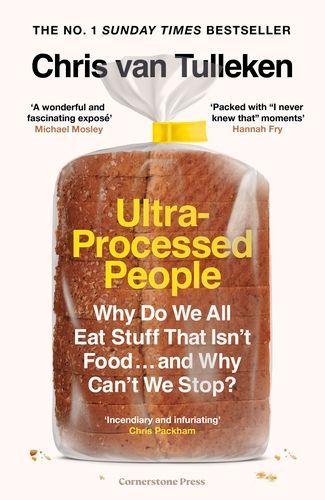

Ultra-Processed People Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food ... and Why Can’t We Stop?

THE NUMBER ONE SUNDAY TIMES BESTESLLER 'If you only read one diet or nutrition book in your life, make it this one' Bee Wilson 'A devastating, witty and scholarly destruction of the shit food we eat and why' Adam Rutherford --- An eye-opening investigation into the science, economics, history and production of ultra-processed food. It's not you, it's the food. We have entered a new 'age of eating' where most of our calories come from an entirely novel set of substances called Ultra-Processed Food, food which is industrially processed and designed and marketed to be addictive. But do we really know what it's doing to our bodies? Join Chris in his travels through the world of food science and a UPF diet to discover what's really going on. Find out why exercise and willpower can't save us, and what UPF is really doing to our bodies, our health, our weight, and the planet (hint: nothing good). For too long we've been told we just need to make different choices, when really we're living in a food environment that makes it nigh-on impossible. So this is a book about our rights. The right to know what we eat and what it does to our bodies and the right to good, affordable food.

Reviews

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Fasiha🌺🐧@faszari98

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Ben@bingobongobengo

Anton Sten@antonsten

Will Dawson@willdawson

Kebo@kebo

Nicole Elora@nicoleelora

Jaclyn Rye@jackierabbit

Navya R@navyarav

Dalia Ergas@dalia

Oliver Magnanimous@oliverm

James Greeley@jamesgreeley

Karolina Klermon-Williams@ofloveandart

Highlights

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop

Laura Dobie@MovingToyshop