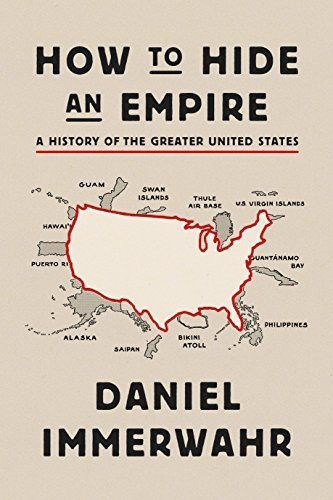

How to Hide an Empire A History of the Greater United States

A pathbreaking history of the United States’ overseas possessions and the true meaning of its empire We are familiar with maps that outline all fifty states. And we are also familiar with the idea that the United States is an “empire,” exercising power around the world. But what about the actual territories—the islands, atolls, and archipelagos—this country has governed and inhabited? In How to Hide an Empire, Daniel Immerwahr tells the fascinating story of the United States outside the United States. In crackling, fast-paced prose, he reveals forgotten episodes that cast American history in a new light. We travel to the Guano Islands, where prospectors collected one of the nineteenth century’s most valuable commodities, and the Philippines, site of the most destructive event on U.S. soil. In Puerto Rico, Immerwahr shows how U.S. doctors conducted grisly experiments they would never have conducted on the mainland and charts the emergence of independence fighters who would shoot up the U.S. Congress. In the years after World War II, Immerwahr notes, the United States moved away from colonialism. Instead, it put innovations in electronics, transportation, and culture to use, devising a new sort of influence that did not require the control of space. Rich with absorbing vignettes, full of surprises, and driven by an original conception of what empire and globalization mean today, How to Hide an Empire is a major and compulsively readable work of history.

Reviews

Winter@countessa

Andrew John Kinney@numidica

Shona Tiger@shonatiger

Taylor@taylord

Vivian@vivian_munich

Caitlin Snyder@caitlinrose

Sahi K@sahibooknerd

Mataia@carlyfaejepsen

N@250cosmos

Cody Degen@codydegen

Rob@robcesq

D VA@pneumatic

Elliott Mower@drmower

Damon Jablons @damo

Alyssa Mastrocco@alyssaa

Jimmy Cerone@jrcii

Lillian@alilbithere

Jillian Clare@wherethelostboysmet

Julius Gehrig@julius

Ethan Hill@localhero

Audrey Kalman@audkal

Evan Huang@eh04

Caitlyn Baldwin@caitlynkbaldwin

Cindy Lieberman@chicindy

Highlights

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle