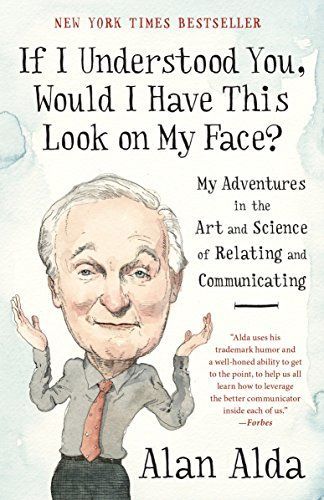

If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

"The actor and founder of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science traces his personal quest to understand how to relate and communicate better, from practicing empathy and using improv games to storytelling and developing better intuitive skills."--Publisher.

Reviews

Justin Jerome Price@so64

Nick Gracilla@ngracilla

Sierra Nguyen@sierra-reads

Safiya @safiya-epub

Erik Horton@erikhorton

Kristen Domonkos @kdomo13

Aaron Long@along