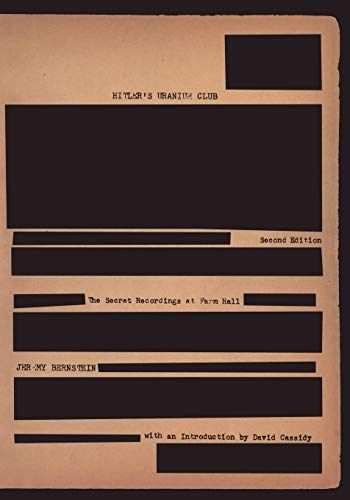

Hitler’s Uranium Club The Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

Near the end of World War II, ten of Germany's foremost nuclear physicists, including Werner Heisenberg, were captured and detained for six months at Farm Hall, an English country house outside Cambridge. This book contains the complete annotated transcripts that were made from secret recordings of their conversations.

Reviews

Gavin@gl