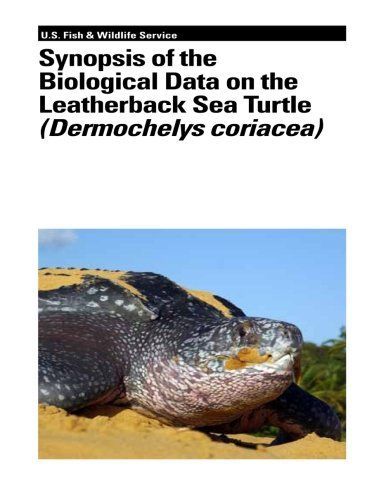

Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys Coriacea)

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea; leatherback) is the largest and most migratory of the world's turtles, with the most extensive geographic range of any living reptile. This highly specialized turtle is the only living member of the family Dermochelyidae. It exhibits reduced external keratinous structures: scales are temporary, disappearing within the first few months and leaving the entire body covered by smooth black skin. Dorsal keels streamline a tapered form. The species has a shallow genealogy and strong population structure worldwide, supporting a natal homing hypothesis. Gravid females arrive seasonally at preferred nesting grounds in tropical and subtropical latitudes, with the largest colonies concentrated in the southern Caribbean region and central West Africa. Non-breeding adults and sub-adults journey into temperate and subarctic zones seeking oceanic jellyfish and other soft-bodied invertebrates. Long-distance movements are not random in timing or location, with turtles potentially possessing an innate awareness of profitable foraging opportunities. The basis for high seas orientation and navigation is poorly understood. Studies of metabolic rate demonstrate marked differences between leatherbacks and other sea turtles: the “marathon” strategy of leatherbacks is characterized by relatively lower sustained active metabolic rates. Metabolic rates during terrestrial activities are well-studied compared with metabolic rates associated with activity at sea. The species faces two major thermoregulatory challenges: maintaining a high core temperature in cold waters of high latitudes and/or great depths, and avoiding overheating in some waters and latitudes, especially while on land during nesting. The primary means of physiological osmoregulation are the lachrymal glands, which eliminate excess salt from the body. The leatherback was re-classified in 2000 by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered. It remains vulnerable to a wide range of threats, including bycatch, ingestion of and entanglement in marine debris, take of turtles and eggs, and loss of nesting habitat to coastal processes and beachfront development. There is no evidence of significant current declines at the largest of the Western Atlantic nesting grounds, but Eastern Atlantic populations face serious threats and Pacific populations have been decimated. Incidental mortality in fisheries, implicated in the collapse of the Eastern Pacific population, is a largely unaddressed problem worldwide. Although sea turtles were among the first marine species to benefit from legal protection and concerted conservation effort around the world, management of contemporary threats often falls short of what is necessary to prevent further population declines and ensure the species' survival throughout its range. Successes include regional agreements that emphasize unified management approaches, national legislation that protects large juveniles and breeding-age adults, and community-based conservation efforts that offer viable alternatives to unsustainable patterns of exploitation. Future priorities should include the identification of critical habitat and priority conservation areas, including corridors that span multiple national jurisdictions and the high seas, the creation of marine management regimes at ecologically relevant scales and the forging of new governance patterns, reducing or eliminating causal factors in population declines (e.g., over-exploitation, bycatch), and improving management capacity at all levels.