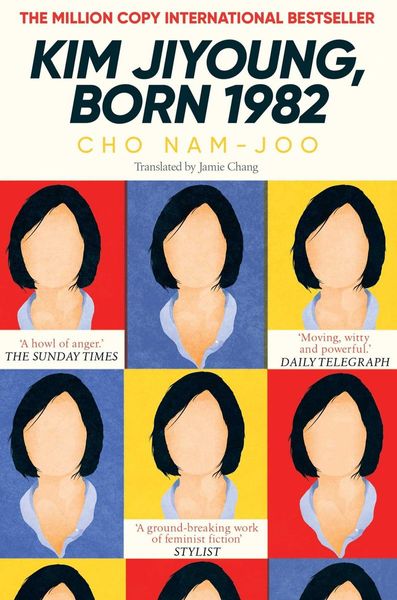

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982

Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 (Korean: 82년생 김지영) is a novel by Cho Nam-Joo. A former scriptwriter for TV programs, Cho took two months to write the story as according to her, the title character "Kim Ji-young's life isn't much different from the one I have lived. That's why I was able to write so quickly without much preparation." Published by Minumsa in October 2016, it has sold more than 1 million copies as of 27 November 2018, becoming the first million-selling Korean novel since Shin Kyung-sook's Please Look After Mom in 2009.

Reviews

星光@teacups

Max Riley@maxreads

Saffia@saffia

jen@seastruck

Stas@stasreads333

Nastenka@deerprose

Paz@pazingaa

catto fishu@catfish-lo

Danniella@danniellaval

elinabel hidalgo @cookiejar

cee @ceereading

joana ashley@whaliensong

Mira <3@siyamira

Eva Ströberg@cphbirdlady

Camilla@camimix

Liz@lizetteratura

safs@safsreads

Louisa@louisasbookclub

EJ@elijahs

Madrid@kntrolla

armoni mayes@armonim1

Natalia Cerrillo@natoodle

Anjorin Molayo @bookishtems

Bria@ladspter

Highlights

Saffia@saffia

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

jen@seastruck

aemouh@aemouh

Aurore@dawnreads

Autumn @rabbit-hearted-reader

Autumn @rabbit-hearted-reader

Autumn @rabbit-hearted-reader

Autumn @rabbit-hearted-reader

Autumn @rabbit-hearted-reader

Lindy@lindy

Lindsay Ornedo@lind_saythename

Lindsay Ornedo@lind_saythename

Lindsay Ornedo@lind_saythename

Lindsay Ornedo@lind_saythename

Lindsay Ornedo@lind_saythename

tuna@tuna9