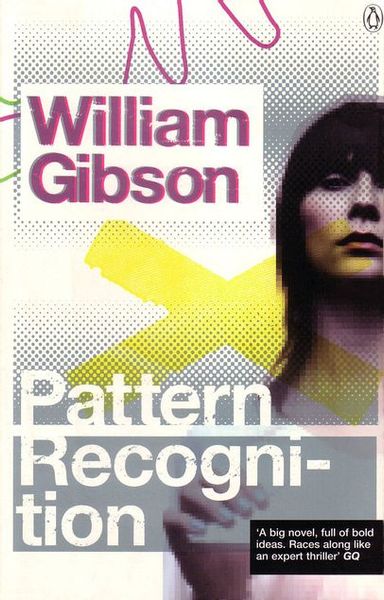

Pattern Recognition

It's only called paranoia if you can't prove it. Cayce is in London to work. Her pathological sensitivity to brands makes her the perfect divining rod for an ad agency that wants to east a new logo. But when she is co-opted into the search for the creator of a strangely addictive on-line film, Cayce wonders if she has done the right - or indeed, safe - thing. And that's before violence, Japanese computer crazies and Russian Mafia men are in the mix. But she wants to discover the source of the film too, and the truth of her father's disappearance in New York, two years ago. And from the way people are trying to stop her, it looks like she's getting close . . .

Reviews

Frederik De Bosschere@freddy

Jeff James@unsquare

Janice Hopper@archergal

里森@lisson

Nat Welch@icco

Daryl Houston@dllh

Daniel Sollero@dsollero

Phil James@philjames

Benjamin Lorenz@bennyurban

mbbs@mbbs

Sherry@catsareit

Lovro Oreskovic@lovro

John Manoogian III@jm3

Pierre@pst

chris@pianogoth

Will Vunderink@willvunderink

Aaron J Mitchell@captainacrab

Hannah Swithinbank@hannahswiv

Ed Macovaz@edmacovaz

Christine Bower@cabower

DANA@creohn

Coleman McCormick@coleman

Ashley McFarland@elementaryflimflam

Traci Wilbanks@traci

Highlights

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson

里森@lisson