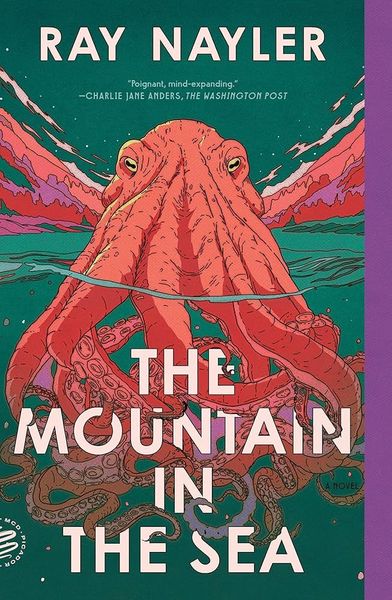

The Mountain in the Sea A Novel

Debut novelist Ray Nayler has written one of the most masterful science fiction novels to come along in some time. This near-future thriller takes place mostly on an archipelago off the coast of Vietnam, where a species of octopus appears to be developing culture. A multinational tech company has purchased and sealed off the islands for further study, and Dr. Ha Nguyen is there to research the creatures. There are others on the team, including Evrim, who is the first humanoid artificial intelligence to have been created, and indeed every character in this novel adds substantially to the story. I’ll be honest: I felt like this book broke my brain several times. It’s just so profound and well written. Ultimately, it’s a study of culture, language, consciousness, and the nature of intelligence, as well as a rumination on ambition and how we treat the world. It’s lyrical and thoughtful, and I'll immediately pick up the next Ray Nayler novel as soon as it’s available. —Chris Schluep, Amazon Editor

Reviews

Katelyn Caillouet@hellokatelyn

abi a@abiblu

julia@juliwaves

Katy Watkins@katy

claire@calorie

Jay Harris@jayharris

Emiley Jones@emileyjones

Brett Seybert@brseybert

Quinnie@ghostkingsss

Laura@laura-itw

Thi Chinh@thichinh

Ridwan Alim Muhaimin@ridwanmhn

Brian Alderman@brianaalderman

Gonia Cholewa@coconuthooves

Jovanna Briscoe @jobrisk

Jeanne L Collier@jeannelynne24

Thomas@tomlinde

Chris Mock@thechrismock

Jason Pinto@jasonpinto

Heath@backpacking_tortoise

Annabelle Gauthier@annagoatcheese

Graham@anagraham

Adam@looptem

anna g@greenbeanseason

Highlights

abi a@abiblu

Page 45

Katy Watkins@katy

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 287

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 287

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 286

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 271

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 267

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 236

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 235

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 233

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 231

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 229

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 227

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 222

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 211

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 209

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 204

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 183

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 167

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 149

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 111

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 76

Giovanni Silva@wamblyreader

Page 73