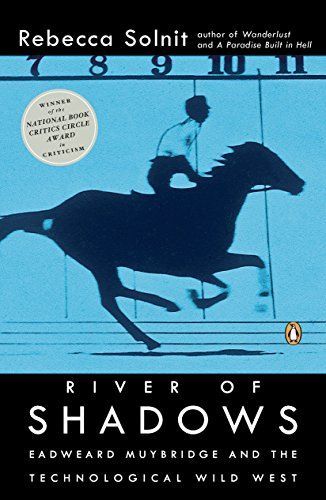

River of Shadows Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West

A survey of the historical contributions of Eadweard Muybridge documents his role in filmmaking technology and as a war photographer before standing trial for the murder of his wife's lover, tracing how his life reflected America in the nineteenth century. Reprint. 25,000 first printing.

Reviews

Bryan Alexander@bryanalexander

Ashley Johnson@ashvalejohn

Andrew Louis@hyfen