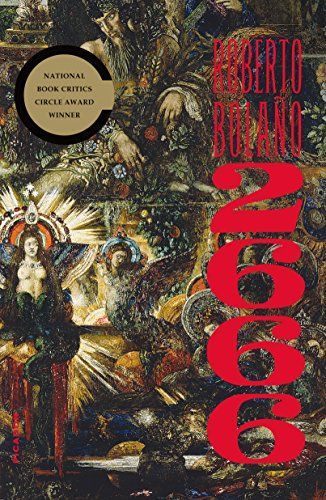

2666

Meesterwerk van de Chileense auteur Roberto Bolaño, wiens oeuvre wij met ingang van dit najaar (opnieuw) zullen uitgeven, te beginnen met deze postuum verschenen roman die wordt gezien als Bolaño's magnum opus: een hallucinerende, epische roman gesitueerd in de grensstreek tussen Mexico en de Verenigde Staten, waar voortdurend vrouwen en meisjes worden vermoord. Niemand weet wie achter de (honderden) moorden zit: de maffia, een psychopaat, de overheid? 2666 is een universeel verhaal over goed en kwaad, leven en dood, fictie en feit, een van de belangrijkste romans die deze eeuw zijn verschenen.

Reviews

Luc Jeanson@captainslatt

kentuckymeatshower@kentuckymeatshower

Ghee@clubsoda

Eli Alvah Huckabee@elijah

Patrick Book@patrickb

Miles Silverstein@thewaxwingslain

Rohan Uddin@thesparrowfall

Jordan Card@origintales

Nelson Zagalo@nzagalo

Lis@seagull

Donald@riversofeurope

Donald@riversofeurope

Donald@riversofeurope

Landen Angeline@landen

Maria José Sandoval@majosandoval

Fernando Andrade@elfre

Melody Izard@mizard

Phil James@philjames

Alithea@alithea

Roland Bekk@ilorkkeb

Alyssa C Smith@alyssacsmith

Yasemin@yerdem

Morgen Ruff@morgen__ruff

Barbara Guerrero@oddityMX

Highlights

Eli Alvah Huckabee@elijah

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Edward Steel@eddsteel

Jordan Card@origintales