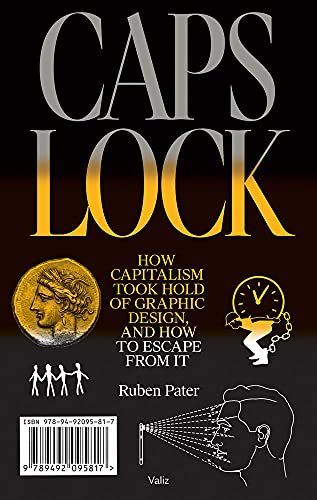

Caps Lock How Capitalism Took Hold of Graphic Design, and How to Escape from It

Capitalism could not exist without the coins, banknotes, documents, information graphics, interfaces, branding, and advertisements made by graphic designers. Even anti-consumerist strategies such as social design and speculative design are appropriated to serve economic growth. It seems design is locked in a cycle of exploitation and extraction, furthering inequality and environmental collapse. CAPS LOCK uses clear language and visual examples to show how graphic design and capitalism are inextricably linked. The book features designed objects and also examines how the study, work, and professional practice of designers support the market economy. Six radical design cooperatives are featured that resist capitalist thinking in their own way, hoping to inspire a more socially aware graphic design.

Reviews

Seyfeddin Başsaraç@seyfeddin

Karolina@fox

taylor miles hopkins@bibette

Isabella Chiara Vicco @isabellachiarav

Krystal@demonhour

Eric L. H.@eric

Morgen Ruff@morgen__ruff

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Inês Pinto@ines

Ines Perez@inesvhperez

Erin Peace@erinpeace

Eleni Agapis@agapisev

Juan Felipe@jfcr

Danilo Campos@daniloc

Olivier Estévez@olivier

James Madson@jamesmadson

Highlights

Krystal@demonhour

Krystal@demonhour

Krystal@demonhour

Krystal@demonhour

Krystal@demonhour

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

Joasia Fidler-Wieruszewska@fidlerowna

taylor miles hopkins@bibette

Page 200

taylor miles hopkins@bibette

Page 191

taylor miles hopkins@bibette

Page 183