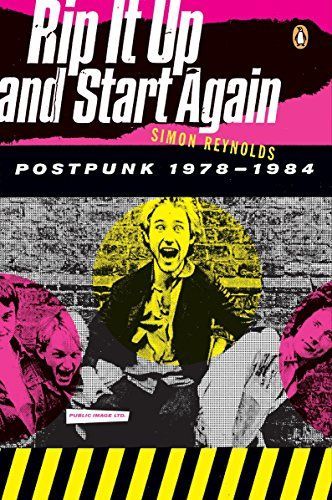

Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978-1984

Rip It Up and Start Again is the first book-length exploration of the wildly adventurous music created in the years after punk. Renowned music journalist Simon Reynolds celebrates the futurist spirit of such bands as Joy Division, Gang of Four, Talking Heads, and Devo, which resulted in endless innovations in music, lyrics, performance, and style and continued into the early eighties with the video-savvy synth-pop of groups such as Human League, Depeche Mode, and Soft Cell, whose success coincided with the rise of MTV. Full of insight and anecdotes and populated by charismatic characters, Rip It Up and Start Again re-creates the idealism, urgency, and excitement of one of the most important and challenging periods in the history of popular music.

Reviews

Gavin@gl