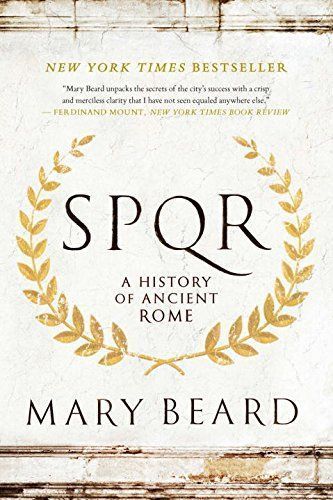

SPQR A History of Ancient Rome

New York Times Bestseller National Book Critics Circle Finalist Wall Street Journal Best Books of 2015 Kirkus Reviews Best Books of 2015 Economist Books of the Year 2015 New York Times Book Review 100 Notable Books of 2015 A sweeping, "magisterial" history of the Roman Empire from one of our foremost classicists shows why Rome remains "relevant to people many centuries later" Atlantic). "

Reviews

Barbara@brubru

Jamieson@jamiesonk

Arun Khanna@kilgoretrout

Matthew Serrano@mserrano

Elizabeth Neill@beersbooksandboos

Nelson Zagalo@nzagalo

Emmett@rookbones

Pascual@ecam

Tanja Rintala@tanjarintala

Ben S@beseku

Tobias V. Langhoff@tvil

D VA@pneumatic

Michael Ernst@beingernst

Andrei Stanciu@andreistanciu

Alan@alancph

Daniel Gynn@danielgynn

Georgi Mitrev@gmitrev

Eugenia Macedo Orozco@eugeniamacedo

Siddharth Ramakrishnan@siddharthvader

Andrew Louis@hyfen

Laura Griffin@laurawiththecurlyhair

Dean Sas@dsas

Isobel @isobel_1711

Jacob Mishook@jmishook

Highlights

Razi Syed@razi

Razi Syed@razi

Razi Syed@razi

Razi Syed@razi

Razi Syed@razi