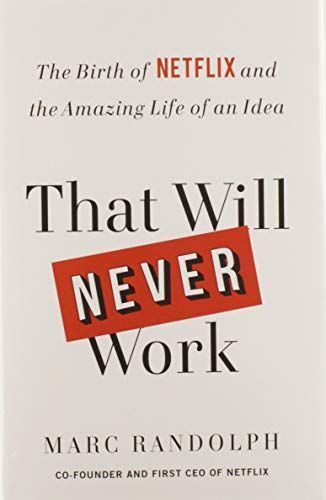

That Will Never Work The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea

In the tradition of Phil Knight's Shoe Dog comes the incredible untold story of how Netflix went from concept to company-all revealed by co-founder and first CEO Marc Randolph. Once upon a time, brick-and-mortar video stores were king. Late fees were ubiquitous, video-streaming unheard of, and widespread DVD adoption seemed about as imminent as flying cars. Indeed, these were the widely accepted laws of the land in 1997, when Marc Randolph had an idea. It was a simple thought-leveraging the internet to rent movies-and was just one of many more and far worse proposals, like personalized baseball bats and a shampoo delivery service, that Randolph would pitch to his business partner, Reed Hastings, on their commute to work each morning. But Hastings was intrigued, and the pair-with Hastings as the primary investor and Randolph as the CEO-founded a company. Now with over 150 million subscribers, Netflix's triumph feels inevitable, but the twenty first century's most disruptive start up began with few believers and calamity at every turn. From having to pitch his own mother on being an early investor, to the motel conference room that served as a first office, to server crashes on launch day, to the now-infamous meeting when Netflix brass pitched Blockbuster to acquire them, Marc Randolph's transformational journey exemplifies how anyone with grit, gut instincts and determination can change the world-even with an idea that many think will never work. What emerges, however, isn't just the inside story of one of the world's most iconic companies. Full of counter-intuitive concepts and written in binge-worthy prose, it answers some of our most fundamental questions about taking that leap of faith in business or in life: How do you begin? How do you weather disappointment and failure? How do you deal with success? What even is success? From idea generation to team building to knowing when it's time to let go, That Will Never Work is not only the ultimate follow-your-dreams parable, but also one of the most dramatic and insightful entrepreneurial stories of our time.

Reviews

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

henrique@kotroby

Felipe Saldarriaga @felipesaldata

Jonathan Filbert@jfl

Christian Beck@cmbeck

Sebastian Stockmarr@stockmarr

James Thorburn@colabeard

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Moksh Garg@mokshgarg003

Arihant Verma@arihant

Joost Reus@joost

Ricardo@ricardobarbosa

Ivan@naviche

Diana Irimia@diana21

Matija@matijao

Yuval Shoshan@yuvals

Róbert Istók@robertistok

Mac Navarro@1xmac

Fan @frankbaozhu

Swarnim Walavalkar@swarnim

Keven Wang@kevenwang

Ben Roberts@benjammin

Martin@martin_dasso

Tomek Skupiński@tomekskupinski

Highlights

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Cassandra Tang@tangaroo

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Page 31

Dhrumil Patel@dhrumil

Page 8

Piet Terheyden@piet

Piet Terheyden@piet

Piet Terheyden@piet

Piet Terheyden@piet

Piet Terheyden@piet

Piet Terheyden@piet