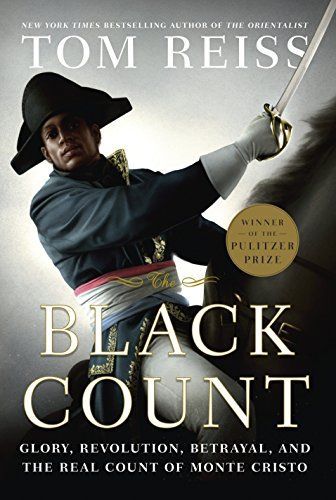

The Black Count Glory, revolution, betrayal and the real Count of Monte Cristo

WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE FOR BIOGRAPHY 2013 ‘Completely absorbing’ Amanda Foreman 'Enthralling’ Guardian ‘The Three Musketeers! The Count of Monte Cristo! The stories of course are fiction. But here a prize-winning author shows us that the inspiration for the swashbuckling stories was, in fact, Dumas’s own father, Alex - the son of a marquis and a black slave... He achieved a giddy ascent from private in the Dragoons to the rank of general; an outsider who had grown up among slaves, he was all for Liberty and Equality. Alex Dumas was the stuff of legend’ Daily Mail So how did such this extraordinary man get erased by history? Why are there no statues of ‘Monsieur Humanity’ as his troops called him? The Black Count uncovers what happened and the role Napoleon played in Dumas’s downfall. By walking the same ground as Dumas - from Haiti to the Pyramids, Paris to the prison cell at Taranto – Reiss, like the novelist before him, triumphantly resurrects this forgotten hero. ‘Entrances from first to last. Dumas the novelist would be proud’ Independent ‘Brilliant’ Glasgow Herald

Reviews

altlovesbooks@altlovesbooks

rumbledethumps@rumbledethumps

Jason Porterfield@katzenpatsy

Jeni Enjaian@jenienjaian

Bryan Alexander@bryanalexander

Abby T. Miller@hairboat

Alisha @theawardshow

Jane McCullough@janemccullough

Emily K McCullar@mccullarmebad

Allison Francis@library_of_ally

Moray Lyle McIntosh@bookish_arcadia

Lloyd Dalton@daltonlp

Frederik Trojaborg Grunwald Julian@frederikjulian

Anna Pinto@ladyars