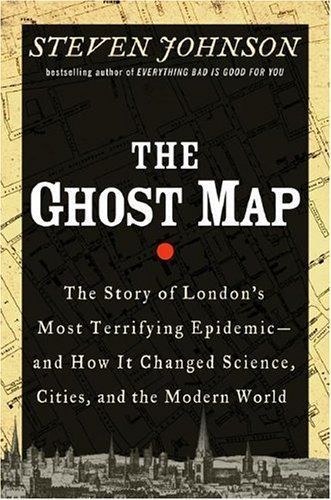

The Ghost Map The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic--and how it Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World

A historical chronicle of Victorian London's worst cholera outbreak traces the day-by-day efforts of Dr. John Snow, who put his own life on the line in his efforts to prove his previously dismissed contagion theory about how the epidemic was spreading. 80,000 first printing.

Reviews

Cindy Lieberman@chicindy

Amanda Valentin@valentin07

Kerry Gibbons@kerryiscool

Jeremy Anderberg@jeremyanderberg

Emily C Peterson@etrigg

Ben Blumenrose@blumenrose

Helen Bright@lemonista

Ryan Mateyk@the_rybrary

John Manoogian III@jm3

Kemie G@kemie

Pierke Bosschieter@pierke

Kaylee@kayleerodenberg

Juliana@soundly

Janice Hopper@archergal

Laura@lauragh

Sara Piteira @sararsp

GP@golp

Jayme Bosio@jaymeb

Loretta Dredger@lorettacd

Genevieve Soucek@gsoucek

Tony Scida@tonyskyday

Amy Bley@enginerdgirl

Alison@inkymathematician

Kali Olson@kaliobooks