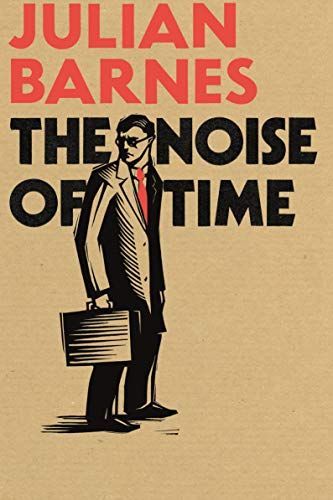

The Noise of Time

In May 1937 a man in his early thirties waits by the lift of a Leningrad apartment block. He waits all through the night, expecting to be taken away to the Big House. Any celebrity he has known in the previous decade is no use to him now. And few who are taken to the Big House ever return. So begins Julian Barnesâe(tm)s first novel since his Booker-winning The Sense of an Ending. A story about the collision of Art and Power, about human compromise, human cowardice and human courage, it is the work of a true master.

Reviews

harvey@harvey-is-asleep

Charles Siboto@charles_s

Emmett@rookbones

Brandon Eckroth@brandoneckroth

Ricky Burgess@rrricky

Hannah Swithinbank@hannahswiv

Hanna Tillmanns @verana79

Ioana Kardos@ioanakardos

Ivan Shiel@barkingstars

Sara Piteira @sararsp

Greta G.@gretaetoya

Alice Uzzan@aliceuzzan

Mutter@mutter

Sabine Delorme@7o9

Savas Yazici@savas

Brooks Bradley Leete@brooks

Liam Byrne @tvtimelimit

Barry Hess@bjhess

Kieran Richards@jebrichards

lizbet koval@lizbetkoval

Steven O'Toole@osteven

Moray Lyle McIntosh@bookish_arcadia

André Nóbrega@anobrega85

Trevor Berrett@mookse