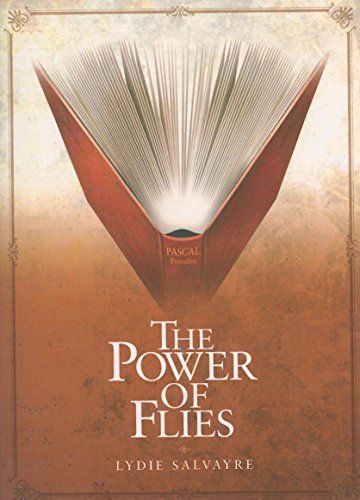

The Power of Flies

The Power of Flies begins in a courtroom, where a man is undergoing an interrogation. He has committed a crime, and he must now explain himself. But instead of letting the judge, lawyer, and psychiatrist question him, he asks himself all the questions—and answers them. While ranting on to the court about various topics—his family, the museum where he works as a tour guide, and even the French philosopher and mathematician, Blaise Pascal—the narrator of The Power of Flies reveals himself to be both calculating and unstable. In this latest novel from acclaimed French writer Lydie Salvayre, it is up to the reader to sort through his philosophical diatribe to discover why this man turned killer. "Salvayre's work applies a cheerful irony to very dark preoccupations: chiefly the connection between political repression and family horrors, and the male sickness of authoritarianism. . . . Salvayre is a writer with a mission."London Review of Books "There are innocuous books that charm you, gently surprise you at moments you didn't expect, blissfully put you to sleep, make you dream of princes and princesses. . . . But there are others, like Lydie Salvayre's novels, that make you sit up and take notice, that directly confront you, that shake you up from the very first sentence, warning you that the test is going to be brutal, the dream is going to be dark, and the princess's smile is going to be painful."Le Monde,/P> "Never a false note. . . . One of France's most virtuosic young novelists."Publishers Weekly "A Parisian museum tour guide descends into madness and murder, guided by the works of the philosopher Blaise Pascal, in this distinctive novel published in France in 1995. Salvayre (The Company of Ghosts) has constructed a bleak character study through which she examines the nature of criminality and the way the past conspires to consume our souls. The narrator, held for the murder of an unnamed victim, reveals his story in conversations with the judge, a psychiatrist, and a guard in the jail's infirmary. Through anecdotes about his workplace (the abbey at Port-Royal des Champs, associated with Pascal and the Jansenist movement) and his failing marriage and his memories of a dismal childhood, we see a man struggling 'to gain a foothold in the void.' Ruminations on the futility of existence place this squarely in the tradition of the French existentialists: in a nod to Camus, the narrator's cellmate is in jail for "killing an Arab." There are also echoes of Don Quixote in the flashes of absurd humor and the theme of a man led to his destruction by overzealous reading. Throughout, Salvayre handles this ambitious framework with great sangfroid. Recommended for literary fiction collections."Library Journal "A madmans intense soliloquy in a slim, powerful volume by French author Salvayre (Everyday Life, 2006, etc.). The novel opens in a courtroom, where a former museum tour guide stands trial for murder. The accused engages in one-sided debates with his judge, prison guard, lawyer and psychiatrist. The nameless voice remains the novels sole speaker, and though his rants prove that he is not only neurotic but mentally unbalanced, he is surprisingly eloquent and darkly humorous. We soon learn that the narrators childhood haunts him: Abused by his angry father, he grew up in a house of violence, fear and hatred. He came to find a father figure in his museum boss, but was crushed when his mentor didnt understand and eventually refused to tolerate his erratic behavior. He is obsessed with his selfless, protective, now-dead mother, and is unable to love any other woman. He had a malfunctioning relationship with his wife, verbally and physically abusive, yet she continued to love him—a fact that irritated him to no end. The condemned mans mocking descriptions of social norms and everyday actions (sex, sneezing) is humorous, and his tone, lacking fear and timidity, can be captivating. The accused may be neurotic, self-involved, snobbish and unlikable, but the questions he raises are universal. What is pre-ordained and what is self-willed? How does one 'gain a foothold in the void'? How much sympathy does one owe his fellow man? Well-composed and provocative."Kirkus