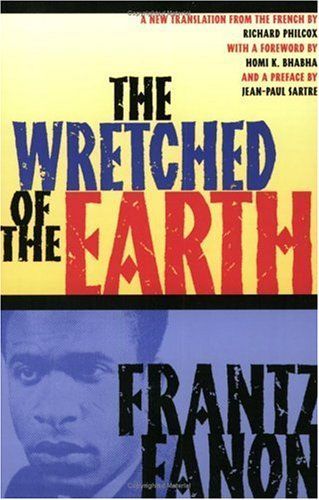

The Wretched of the Earth

A distinguished psychiatrist from Martinique who took part in the Algerian Nationalist Movement, Frantz Fanon was one of the most important theorists of revolutionary struggle, colonialism, and racial difference in history. Fanon's masterwork is a classic alongside Edward Said's Orientalism or The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and it is now available in a new translation that updates its language for a new generation of readers. The Wretched of the Earth is a brilliant analysis of the psychology of the colonized and their path to liberation. Bearing singular insight into the rage and frustration of colonized peoples, and the role of violence in effecting historical change, the book incisively attacks the twin perils of post independence colonial politics: the disenfranchisement of the masses by the elites on the one hand, and intertribal and interfaith animosities on the other. Fanon's analysis, a veritable handbook of social reorganization for leaders of emerging nations, has been reflected all too clearly in the corruption and violence that has plagued present-day Africa. The Wretched of the Earth has had a major impact on civil rights, anticolonialism, and black consciousness movements around the world, and this bold new translation by Richard Philcox reaffirms it as a landmark.

Reviews

muskaan bal@muskaankb

eris@eris

T@mateitudor

elizabeth@ekmclaren

Zack Dihel@dumb_zack

Alexander Enriquez@kgbkowboy

Ray Remnant@rayremnant

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Erich@erichrc

laia@salemrot

alexa@newjeans

Mikre @mikre

Atticus Cameron@atticspaced

Martha F.@marthaq

yasi@middleschoolbf

Aldrake @hamborger

chai@chaimyto

sky na@otterwott

Olivia@owalsh2

Hannah Swithinbank@hannahswiv

Stan D@tragikistan

emma@yeojinluvr

Amanda Sutter@duhitsamanda

Crystal L@umcrystal

Highlights

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 313

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 309

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 308

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 285

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 199

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 194

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 192

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 191

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 189

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 173

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 139

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 109

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 101

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 99

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 96

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 94

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 84

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 70

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 61

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 54

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 27

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 26

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 23