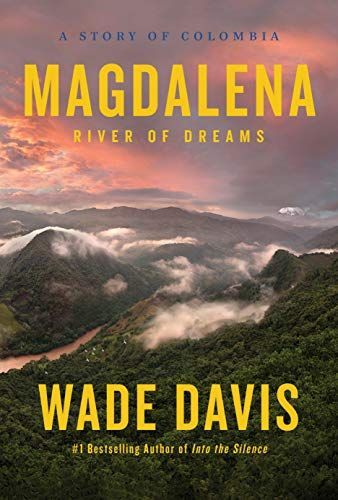

Magdalena River of Dreams

A captivating new book from Wade Davis--award-winning, bestselling author and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence for more than a decade-- that brings vividly to life the story of the great Río Magdalena, illuminating Colombia's complex past, present, and future Travelers often become enchanted with the first country that captures their hearts and gives them license to be free. For Wade Davis, it was Colombia. Now in a masterful new book, the bestselling author tells of his travels on the mighty Magdalena, the river that made possible the nation. Along the way, he finds a people who have overcome years of conflict precisely because of their character, informed by an enduring spirit of place, and a deep love of a land that is home to the greatest ecological and geographical diversity on the planet. Only in Colombia can a traveler wash ashore in a coastal desert, follow waterways through wetlands as wide as the sky, ascend narrow tracks through dense tropical forests, and reach verdant Andean valleys rising to soaring ice-clad summits. This rugged and impossible geography finds its perfect coefficient in the topography of the Colombian spirit: restive, potent, at times placid and calm, in moments explosive and wild. Both a corridor of commerce and a fountain of culture, the wellspring of Colombian music, literature, poetry and prayer, the Magdalena has served in dark times as the graveyard of the nation. And yet, always, it returns as a river of life. At once an absorbing adventure and an inspiring tale of hope and redemption, Magdalena gives us a rare, kaleidoscopic picture of a nation on the verge of a new period of peace. Braiding together memoir, history, and journalism, Wade Davis tells the story of the country's most magnificent river, and in doing so, tells the epic story of Colombia.

Highlights

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano

Stefano Zorzi@stefano