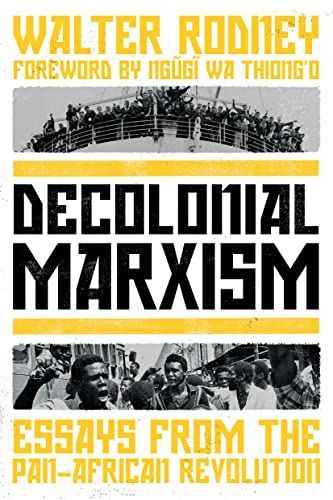

Decolonial Marxism Essays from the Pan-African Revolution

A previously unpublished collection of Rodney's essays on Marxism, spanning his engagement with of Black Power, Ujamaa Villages, and the everyday people who put an end to a colonial era Early in life, Walter Rodney became a major revolutionary figure in a dizzying range of locales that traversed the breadth of the Black diaspora: in North America and Europe, in the Caribbean and on the African continent. He was not only a witness of a Pan-African and socialist internationalism; in his efforts to build mass organizations, catalyze rebellious ferment, and theorize an anti-colonial path to self-emancipation, he can be counted among its prime authors. Decolonial Marxism records such a life by collecting previously unbound essays written during the world-turning days of Black revolution. In drawing together pages where he elaborates on the nexus of race and class, offers his reflections on radical pedagogy, outlines programs for newly independent nation-states, considers the challenges of anti-colonial historiography, and produces balance sheets for a dozen wars for national liberation, this volume captures something of the range and power of Rodney's output. But it also demonstrates the unbending consistency that unites his life and work: the ongoing reinvention of living conception of Marxism, and a respect for the still untapped potential of mass self-rule.

Reviews

Adam Arif-Pardy@arif74

Highlights

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 204

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 202

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 199

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 191

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 181

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 180

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 156

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 145

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 134

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 133

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 121

nhu ⋆𐙚₊˚⊹@nhuelle

Page 109