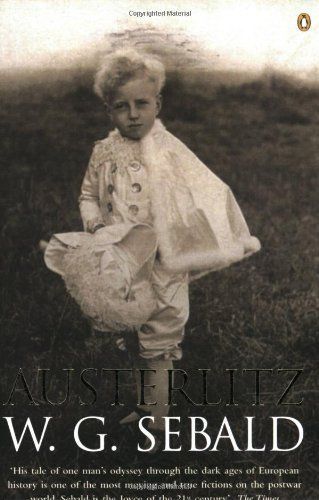

Austerlitz

From one of the undisputed masters of world literature, a haunting novel of sublime ambition and power about a man whose fragmentary memories of a lost childhood lead him on a quest across Europe in search of his heritage. Jacques Austerlitz is a survivor – rescued as a child from the Nazi threat. In the summer of 1939 he arrives in Wales to live with a Methodist minister and his wife. As he grows up, they tell him nothing of his origins, and he reaches adulthood with no understanding of where he came from. Late in life, a sudden memory brings him the first glimpse of his origins, launching him on a journey into a family history that has been buried. The story of Jacques Austerlitz unfolds over the course of a 30-year conversation that takes place in train stations and travellers’ stops across England and Europe. In Jacques Austerlitz, Sebald embodies the universal human search for identity, the struggle to impose coherence on memory, a struggle complicated by the mind’s defences against trauma. Along the way, this novel of many riches dwells magically on a variety of subjects – railway architecture, military fortifications, insects, plants and animals, the constellations, works of art, a small circus and the three cities that loom over the book, London, Paris and Prague – in the service of its astounding vision. From the Hardcover edition.

Reviews

Tom Koss@tkoss

Erfan Abedi@erfan

Lily@variouslilies

Sabine Delorme@7o9

Patricia@hymntojuly

MJ@mikejonesberlin

Mat Connor@mconnor

Elena Kuran@elenakatherine

Andrea Guadalupe@lasantalupita

Jeff Roche@jeffroche

Gordy@gortron

Vanda@moonfaced

Hanna Tillmanns @verana79

Clare B@hadaly

Scordatura@scordatura

Hellboy TCR@hellboytcr009

Jacob Mishook@jmishook

Liz Prinz@prinzy

Brigid Hogan@br1gid

ANDREW BRYK@andrewbryk

Darima@starwanderer

Emily K McCullar@mccullarmebad

Nadia Bailey@preludes

Cem Pekdogru@pekdogru