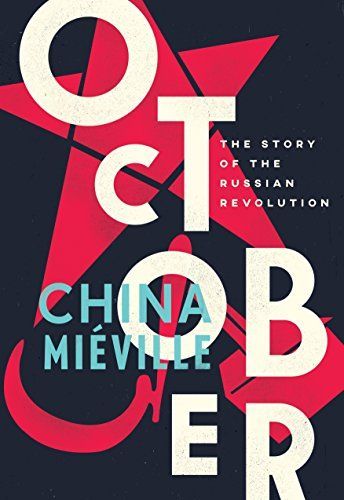

October The Story of the Russian Revolution

Acclaimed fantasy author China Mieville plunges us into the year the world was turned upside down The renowned fantasy and science fiction writer China Mieville has long been inspired by the ideals of the Russian Revolution and here, on the centenary of the revolution, he provides his own distinctive take on its history. In February 1917, in the midst of bloody war, Russia was still an autocratic monarchy: nine months later, it became the first socialist state in world history. How did this unimaginable transformation take place? How was a ravaged and backward country, swept up in a desperately unpopular war, rocked by not one but two revolutions? This is the story of the extraordinary months between those upheavals, in February and October, of the forces and individuals who made 1917 so epochal a year, of their intrigues, negotiations, conflicts and catastrophes. From familiar names like Lenin and Trotsky to their opponents Kornilov and Kerensky; from the byzantine squabbles of urban activists to the remotest villages of a sprawling empire; from the revolutionary railroad Sublime to the ciphers and static of coup by telegram; from grand sweep to forgotten detail. Historians have debated the revolution for a hundred years, its portents and possibilities: the mass of literature can be daunting. But here is a book for those new to the events, told not only in their historical import but in all their passion and drama and strangeness. Because as well as a political event of profound and ongoing consequence, Mieville reveals the Russian Revolution as a breathtaking story."

Reviews

André Nóbrega@anobrega85

Brigid Hogan@br1gid

Bryan Alexander@bryanalexander

Adriana Coppola@adrianaa

César Steven Toribio@cesarsteven

Mitch Stewart@mitchbones

Damon Jablons @damo

Dave Walker@bibliosaurusrex

Savas Yazici@savas

Angelo Zinna@angelozinna

Julia A.@brizna

Moray Lyle McIntosh@bookish_arcadia

Laura Schmidt@lauras

Tim Vos@roquentin

Dani@erudani